Recently I penned a piece about my youngest son Zach, who is on the milder end of the spectrum. I wrote about how he now is only on a 504 plan, not in an inclusion classroom, and doing well both academically and socially. I spoke about the many things that contributed to this outcome, the teachers, therapists, and love that went into helping our boy be as happy and independent as he can possibly be. I explained that my delight had not to do with his ability to engage in the trappings of a more neurotypical life, but that he was now able to participate in so many of the activities he always wanted to be a part of, and that this year more than any other, he was happy. I had many wonderful and supportive comments after the piece was published, and of course, as always, there was one private comment which really stuck with me.

“Can you tell me how you got him there?”

Frankly, it would be fun to take all the credit. I could tell you about the hours of therapy I did with him before school started, the gluten-free casein-free diet (fake cheese is an abomination) we still strictly adhere to, the outside therapies and activities we’ve taken him to to allow him to stretch and grow. I could tell you about the eight million hours I spent reading on the internet and the books I devoured to help him in any way I could. I could wax on about the many times I reminded myself that Zach’s autism is different than Justin’s, and not to be wedded to anything we’d tried with our eldest, but to tailor our treatments to our youngest son’s needs.

|

|

I could tell you about the scrapbooks I made to help him talk again, but that would just be overkill.

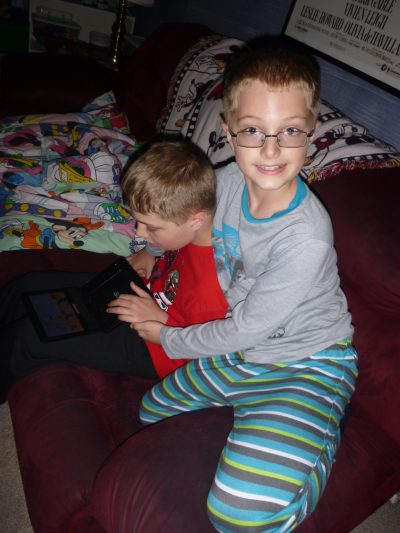

The truth is I have two kids on the spectrum, one severe, one mild (I hate all the labels so I’m sticking with these). I will be perfectly honest with you and share that I did much more for Justin than I did for Zach, and yet my eldest is much more involved and my youngest could be president.

He’s on student council this year. He’s considering a run.

Justin was diagnosed at the tender age of seventeen months, which back in 2004 was basically unheard of. At the time insurance did not pay for ABA services, and Early Intervention in Virginia was a joke, so since I knew that it would be almost two more years until he went to school I hunkered down and did the therapy myself. I cranked out thirty weekly ABA hours with a mostly compliant kid until we moved to New Jersey eighteen months later and walked gratefully into eighty hours a month of therapy (compared to Virginia’s eight). Justin was an only child all that time, and I am not kidding when I tell you I took every “teachable moment” as gospel.

As Erin Brockovitch would say, I was really quite tired.Ten years later my teen is (mostly) happy, does beautifully in school, and when not engaged in severe OCD-behavior is a delight and a joy.

He will never drive, go to college, or live independently despite the eighty million hours of therapy and the hard work of everyone who helped us from his toddler years on. He has a few words now but mostly communicates with a device, and the words he has are hard to understand. He’s progressed to the best of his ability, and I am confident he will to continue to do so.

And just because he’s not following his brother’s life trajectory it doesn’t mean we’ve failed him.

I will go to my dying day wishing Justin would be able to take care of himself after his parents’ death. Now that he’s so happy it is probably the one thing left that keeps me up nights. But I know that all of us, him especially, have done the best we could to enable him to be his most independent self.

Honestly I can’t tell you why one of my kids will need lifetime care and the other is not even classified as a special education student anymore, but I can tell you this. We can throw therapy and diets and medications and boundless love at our kids, and all of it will help. In the end however it’s really up to them the progress they make, what their long-term life trajectory will look like (and for any parents starting out, you absolutely cannot know that when they’re three).

The truth is (and this is true of any kid) so much of what they’re able to achieve is up to them, and that includes both ability and motivation, which I can contest from a dozen years in the classroom are equally important. They will do what they can, and accepting that has brought me a great deal of peace over the years.

And at the end of the day, I’m sure we could all use some peace.

For more on my family visit my blog at autismmommytherapist.wordpress.com

Follow me on Facebook at Autism Mommy-Therapist