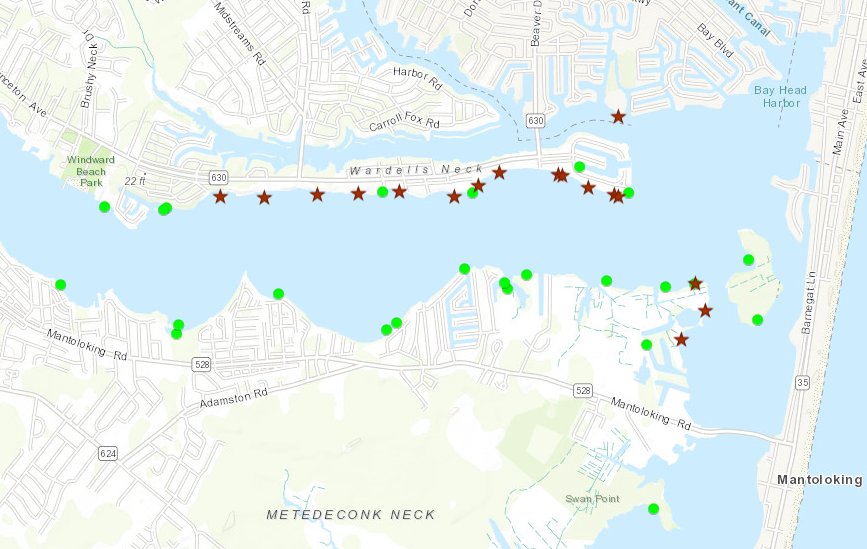

Locations clinging jellyfish have been in northern Ocean County during June 2018 surveys. (Credit: NJDEP/ Montclair State University)

The state Department of Environmental Protection on Friday released data gathered over the last week that showed dangerous clinging jellyfish were found in 17 out of 40 locations surveyed by researchers.

The DEP has partnered with Montclair State University to track the jellyfish, which are about the size of a dime, after they were first discovered in New Jersey waters two years ago. Recent sightings led to a more intense investigation of the presence of the species in local waters, and a swim advisory for the Metedeconk River and Barnegat Bay was issued by the state. That advisory was reiterated and extended on Friday.

The clinging jellyfish, a native to the Pacific Ocean, is small and very difficult to spot in the water. A sting can produce severe pain and other localized symptoms and can result in hospitalization in some individuals. It is called a “clinging” jellyfish because it survives by clinging to the edges of plants and aquatic vegetation. The species is only found in rivers and bays; the advisory does not extend to ocean beaches.

The state published a map on Friday showing where the species had been found over the last week. The vast majority were found along the northern bank of the Metedeconk River, but a few were found in northern Barnegat Bay in an area known as “Gunner’s Ditch,” which is a small channel between sedge islands and the Brick mainland. No jellyfish were found in F-Cove or Traders Cove Marina, the data showed, both popular spots for boaters. One jellyfish was found outside of F-Cove, but another search inside in the cove had negative results.

The DEP and Montclair researchers will continue monitoring the population but “there is no method to effectively control clinging jellyfish populations in the aquatic environment,” the DEP said in a statement on Friday.

The clinging jellyfish is much smaller than the sea nettle, a more common species that is little more than a nuisance. Sea nettles, which produce a less powerful sting, are common in Barnegat Bay but are much larger. The good, officials said, is that they prey on clinging jellyfish. The clinging jellyfish ranges from the size of a dime to about the size of a quarter. It has a distinctive red, orange or violet cross across its middle.

Both the adult, or medusa, and polyp stages of the clinging jellyfish are capable of stinging, a mechanism the species uses to stun prey and to defend against predators. Each jellyfish can trail 60 to 90 tentacles that uncoil like sharp threads and emit painful neurotoxins. Tentacles grow to be about three inches long. Clinging jellyfish primarily feed on zooplankton.

Clinging jellyfish do not swim or migrate but can be spread by boats and in ballast. They were first observed in the eastern Atlantic at Woods Hole, Mass. By the 1920s, they had spread to other waterways in Massachusetts and Connecticut, likely through introduction by ship ballast or from Pacific oysters containing polyps.

Environmental officials are seeking the public’s help in tracking clinging jellyfish, but caution is required, they said. If you see a clinging jellyfish, do not try to capture it. Take a photograph if possible and send it to Dr. Paul Bologna at bolognap@mail.montclair.edu or Joseph Bilinski at joseph.bilinski@dep.nj.gov along with location information.

~

If stung by a clinging jellyfish:

- Apply white vinegar to the affected area to immobilize any remaining stinging cells.

- Rinse the area with salt water and remove any remaining tentacle materials using gloves or a thick towel.

- A hot compress or cold pack can then be applied to alleviate pain.

- If symptoms persist or pain increases instead of subsiding, seek prompt medical attention.

Advertisement

Police, Fire & Courts

Grand Jury Indicts Point Pleasant Man, Once a Fugitive, for Attempted Murder