South Drive, part of a peninsula off Princeton Avenue, where clinging jellyfish have been found in 2023. (Photo: Shorebeat)

Last week, state environmental officials warned about the presence of “clinging jellyfish” in the Shore area, setting off a media firestorm that included national television spots on the dime-sized jellyfish that pack an extremely painful punch.

Though the reports were largely accurate, some news consumers may have been left with the idea that clinging jellyfish pose a threat along Atlantic Ocean beaches. But while non-native populations of the jellyfish have been found in far-flung ocean environments like Dry Tortugas, Fla., the Atlantic coast of Portugal and Mar del Plata in Argentina, New Jersey’s unique population has been limited only to back bays.

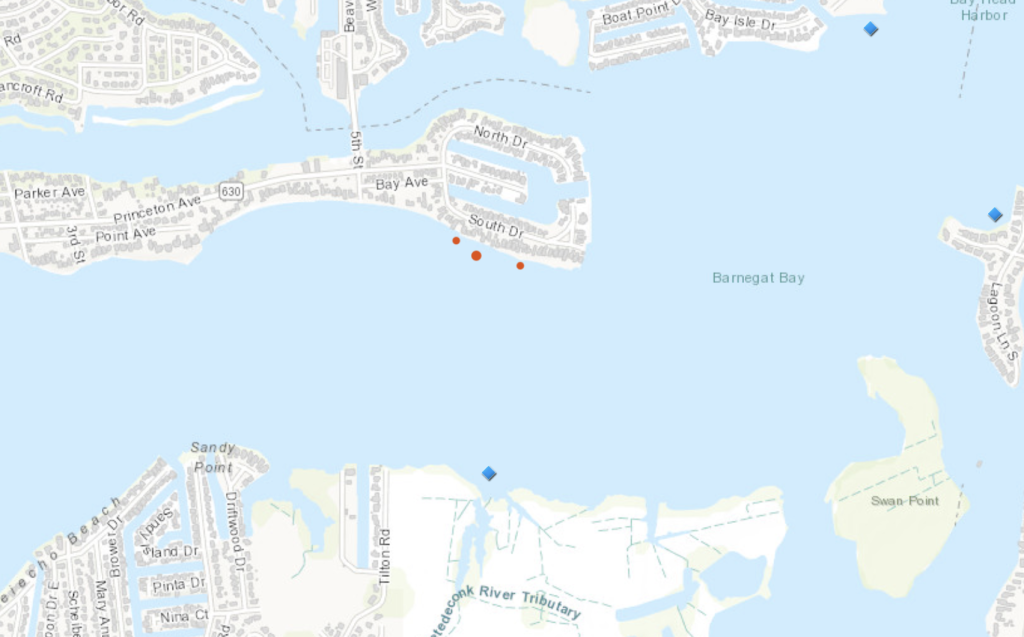

While past seasons have seen the jellyfish detected in parts of northern Monmouth County, the dominant area where the species has been found so far in 2023 has been the mainland side of the bay in Brick Township. Specifically, one of the “hot spots” for the species has been off residential properties along Princeton Avenue, according to mapping software released by the state. Searches closer to areas where swimming is popular with the public, such as F-Cove, has not turned up any clinging jellyfish thus far, but experts warn it is likely some could be there anyway.

|

|

South Drive, part of a peninsula off Princeton Avenue, where clinging jellyfish have been found in 2023. (Photo: Shorebeat)

The Princeton Avenue area – specifically, the waters off South Drive on a peninsula extending from Princeton – saw three sampled areas produce between 11 and 35 jellyfish each. Aerial photography shows seaweed and grasses present in the area.

“Fortunately, populations of clinging jellyfish and their distribution have been largely stable since the species was first confirmed in New Jersey in 2016,” said DEP Commissioner Shawn M. LaTourette. “However, clinging jellyfish pack such a potentially powerful sting that it is important for the public to be vigilant and take precautions when recreating in coastal bays and rivers where they are found.”

But why do these transparent, bell-shaped jellies seem to keep coming back to Brick Township’s northern reaches? The answer may be in the salinity of the water at the confluence of Barnegat Bay, the Metedeconk River and Beaver Dam Creek. Some of these areas, despite being coastal in nature, were freshwater dominant prior to the opening of the Point Pleasant Canal. Once the canal opened, allowing the bay to be “flushed” with salt water on a daily basis, the waters of the Metedeconk and its surrounding creeks became more brackish. The local clinging jellyfish population seems to be attracted to such waters, experts say, though there is wide disagreement as to where the species is invasive and where there were historically native populations that were simply never detected. In addition to those listed above, communities of clinging jellyfish have been found from the waters of the Russian far east to the Mediterranean Sea, and even as far north as Norway.

It is highly unlikely for clinging jellyfish to be found in ocean waters or beaches in New Jersey, the DEP said in its statement last week. Rather, the species prefers shallow, slow-moving estuarine waters, where they attach themselves to algae or marine vegetation such as eel grass. The practice of the species attaching itself to grasses and sunken tree branches led to it being named the “clinging” jellyfish.

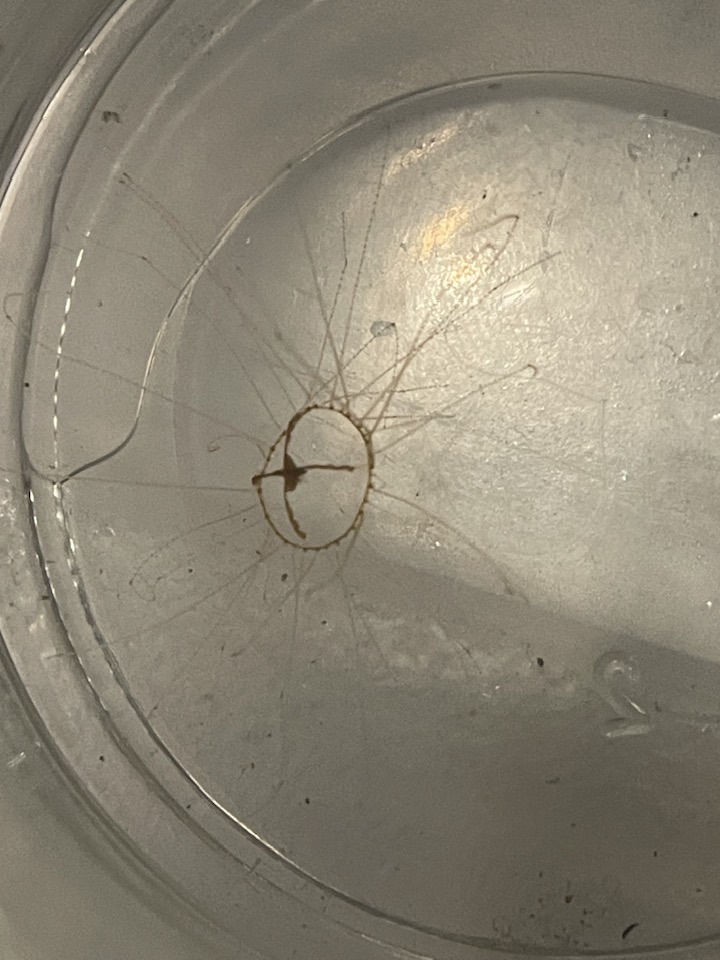

Clinging jellyfish range from the size of a dime to a quarter. Adults are marked by a distinctive reddish-orange to yellowish cross within their translucent bodies. To date, no human being has ever died due to a sting from a clinging jellyfish, said Dr. Paul Bologna, a marine biologist and jellyfish expert at Montclair State University, but they pack an extremely powerful sting that has sent victims to the hospital.

Those who are stung by a clinging jellyfish will experience an initial burning sensation, but in many cases the reaction will get progressively worse before it gets better. The official instructions from the DEP for responding to clinging jellyfish stings include rinsing the area with saltwater and removing any remaining tentacle materials using gloves, a plastic card or a thick towel.

“If symptoms persist or pain increases instead of subsiding, seek prompt medical attention,” the state agency said.

“Clinging jellyfish are small, but they can produce severe pain in people who are stung in the shallow bays of New Jersey and New England,” said Bologna, who has personally conducted jellyfish-finding trips along with his students. “Since we can’t be everywhere, the public is often our best source of information. Many eyes on the water help us confirm new areas where they are located to better inform the public and keep everyone safe.”

The state has said it has dedicated high-tech resources to the detection of the species as well.

A recent study commissioned by the DEP in collaboration with Rutgers University’s Department of Ecology, Evolution, and Natural Resources aims to make it easier to detect the location and monitor the number of various species of cnidarians – a group of animals equipped with stinging cells that includes clinging jellyfish and other types of jellyfish – by testing water samples for their eDNA, which are identifiers found within the water column.

So far this season, clinging jellyfish have been visually confirmed in two locations: the waters of Brick Township, and an area of North Wildwood, in Cape May County.

Previously, clinging jellyfish have been found in several locations including the Metedeconk River, the bayside of Island Beach State Park, the Shrewsbury River, a salt pond in North Wildwood located adjacent to Hereford Inlet Lighthouse, the Lower Township Thorofare (a back bay waterway) and the Cape May National Wildlife Refuge. The jellyfish are found from mid-May to late July, or until bay water temperatures reach or exceed 82 degrees Fahrenheit.

Adult clinging jellyfish prefer to be attached to eelgrass and seaweed during the day but become active in the water column if disturbed and after sunset. If disturbed, they will attempt to reattach to the substrate, which provides shelter and protection.

“Monitoring of invasive species is critical for science and management, especially when they potentially pose a threat to human health,” said Bologna, whose Facebook group “New Jersey Jellyspotters” has grown recently.

The good news for back bay swimmers, however, is that the species usually exits the region by the time the bay water temperature reaches 82 degrees.

Advertisement

Police, Fire & Courts

Grand Jury Indicts Point Pleasant Man, Once a Fugitive, for Attempted Murder