One of Brick Township’s busiest intersections saw over 1,000 crashes involving vehicles in four years, state data showed, while the overall number of crashes involving bicycles and pedestrians in the township reached over 400 during the same time period. This week, officials reviewed ways to improve traffic flow and safety during a special meeting of the planning board to re-examine the Brick’s traffic circulation master plan.

While it may be easy to blame city hall for traffic woes, Brick controls little of its own roadway destiny at the local level. None of the intersections that saw the most crashes over the last several years – and decade – are under municipal jurisdiction. And Brick Township does not operate a single traffic light; every traffic signal in town is either under county or state control. But while these challenges are not going away, board members, the township planner and the board’s engineer discussed what could be done at a local level to make the roads safer.

|

|

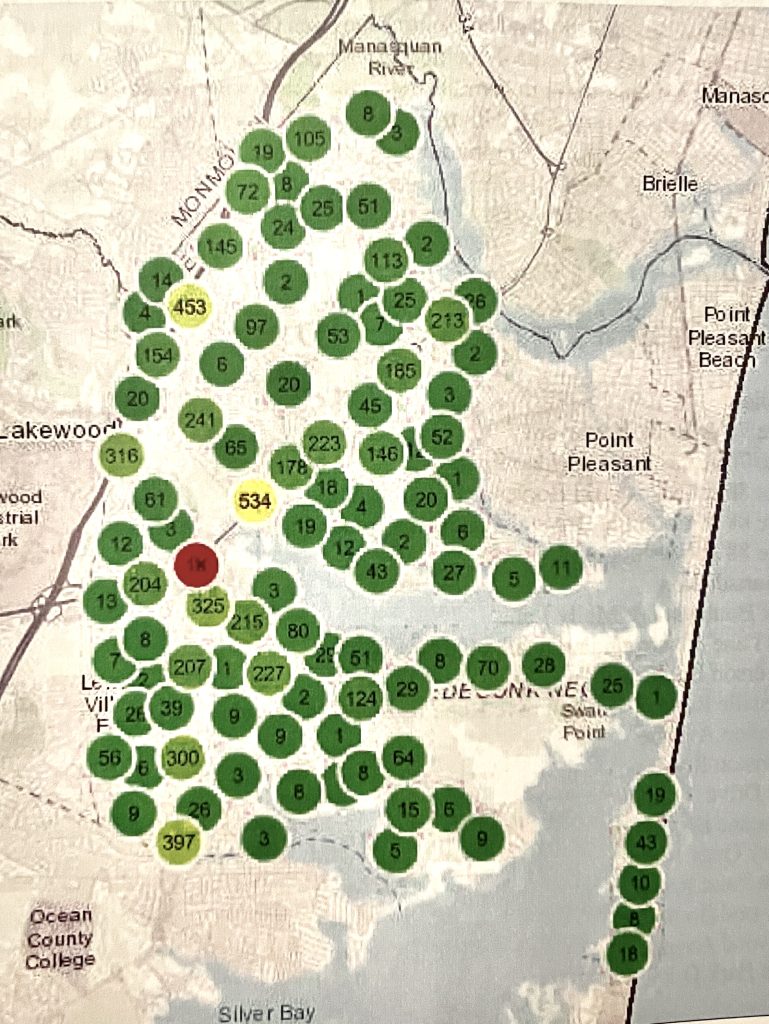

The most dangerous intersection in Brick, measured by the number of crashes, was Route 70 and Chambers Bridge Road, which saw more than 1,000 crashes between 2018 and 2022, according to crash data from a state system utilized by planners and law enforcement. It is represented on a map of the township as a red circle in the middle of town, signifying its status, by far, as the intersection with the highest number of collisions – counting accidents between vehicles and bicyclists and pedestrians struck. The state now uses the term “crash” rather than “accident” in its data.

“They call them crashes now because they’re not just random accidents – they’re not on purpose, but they’re crashes that are looking to be prevented,” said Township Planner Tara Paxton.

That theory is what was behind a state-mandated re-examination of the traffic circulation master plan, a 17-page document that details broad suggestions on how traffic flow can be improved before new development occurs.

The intersection of Route 88, Route 70 and Princeton Avenue in Brick, N.J., Dec. 2023. (Photo: Shorebeat)

Brick’s other high-crash intersections include the confluence of Route 70, Route 88 and Princeton Avenue, with 534 crashes and the area of Burnt Tavern Road at the intersections of Burrsville and Lanes Mill roads, where 453 crashes occurred. Brick Boulevard and Molly Lane saw 397 crashes and Route 70 and Brick Boulevard, where 325 crashes occurred during the same time period.

“One of the keys to understanding the circulation system is to accept that one cannot simply reduce the amount of traffic on our roadways,” the report said. “The solution is efficient traffic management as opposed to traffic reduction. This can be achieved by methods as complex as providing alternate routes to overcrowded highways, or as simple as providing way-finding signage along seasonal or commercial routes.”

The report also calls for traffic calming measures and safety design features to be prioritized during road projects rather than simply adding lanes or widening roads.

“It’s tough here, because we have so much redevelopment and there is so much emphasis on existing sites, it’s rare to have a virgin site where we can take care of these things before development,” said Caroline Reiter, the board’s planning consultant.

The good news, the report found, was that Brick officials tended to focus more on traffic than their counterparts across the state when it comes to reviewing development applications, though snags sometimes occur when a properly-zoned development – such as the Wawa at Route 88 and Jack Martin Boulevard – must be approved by the board even though the board has no jurisdiction over turns into and out of the site since it is located on a state highway. More than two years after Brick officials called for left turns to into the store from the busy highway be prohibited, the state Department of Transportation has yet to mandate the rule.

Still, the report said, Brick has been diligent in applying state traffic laws to the internal lanes of privately-owned shopping centers. Numerous new commercial properties agreed to allow police to enforce the state traffic code on their properties just recently, joining a list of hundreds of such agreements throughout town.

A challenge for Brick, in particular, is that the township developed at varying paces over a period of nearly 50 years, leading to “an assortment of improvements that vary from neighborhood to neighborhood.” The report reiterated that nearly all of the commercial development in town has occurred on state and county roads, which creates its own challenges at the local level when it comes to creating a cohesive traffic management plan.

The report found that at the intersections and roadways with the highest number of crashes, the township council and Brick’s two land use boards – the planning board and zoning board – should consider studying numerous ways to minimize the number of movements of vehicles between roadways and parking lots, as well as implement traffic calming measures. These measure may include:

- The re-striping of pavement markings and new lane configurations.

- The installation of “speed boxes,” electronic tracking systems that perform real-time traffic flow analysis.

- Speed bumps.

- Requiring, where feasible, cross-access easements between commercial properties so vehicles do not have to re-enter a highway to cross between shopping centers.

- Requiring developers to prove why cross-access easements cannot be implemented when they are not proposed, and detailing alternatives.

- Enforcing an existing five-year moratorium on excavating streets and roadways that have recently been improved or re-paved.

- Prohibiting developers from designing projects that reduce the capacity of adjacent roadways to handle the same amount of traffic compared to pre-development levels.

- Updating ordinances to reduce the number of driveways connecting developments to existing roadways and set minimum distances between driveway openings.

“The township should take greater involvement where development on state highways is proposed,” the report said, including codifying traffic calming measures where developments and roadways intersect in order to prevent safety issues before they emerge.

The report also called for numerous intersections to be studied, and for the implementation of a uniform system where officials can track traffic flow data, crash data and citizen complaints to identify particular areas in need of attention.

Ocean County, in its own last re-examination of traffic flow county-wide in 2018, also adopted standards that focus roadway improvements projects on implementing better lane configuration, striping, turning lanes and traffic signals rather than road-widening efforts.

A major concern for Paxton, the township planner, is the significant challenge of reducing crashes involving pedestrians and bicyclists. She suggested the township become more closely involved in Vision Zero, a best-practices program that promotes safety for those walking and biking through town.

“Vision Zero is a movement internationally that talks about how we should be designing roads and transportation routes to achieve no fatalities on any of these facilities,” said Paxton.

While it may not always be feasible, requiring sidewalks and bicycle lanes on new development projects may, over time, increasing the overall capacity of the roadway network to safely accommodate bicycle and pedestrian traffic, she said. Members of planning and zoning boards, she suggested, should have access to site-specific traffic data from the state’s Voyager database, a software application that serves as a clearinghouse for managing crash data. This could involve working more closely with the police department, which prepares much of that data.

“If we have an application on a road where the neighbors are discussing a lot of crashes, we can call on them to pull down that information so you’ll [board members] have that, and we might be able to improve the traffic situation in the area of an application,” Paxton said.

There could also be ordinance changes that would mandate considerations for bicycle and pedestrian traffic.

“Maybe we should consider taking it a step further and make it mandatory that a bicycle lane be incorporated in the front of properties,” said Reiter.

On the other hand, “Obtaining state rights-of-way as municipal rights-of-way can come with a large cost,” said Paxton, and developers cannot unilaterally install bicycle lanes on property which they do not own or cannot access. In many cases along state roadways, the state’s right-of-way extends 150-feet in width, and may have to be purchased by the township.

Paxton promoted the “Complete Streets” concept, wherein extra consideration is given to bicycle lanes, pedestrian access points, and the needs of “users who have been historically forgotten in the design of roads,” such as senior citizens, disabled residents and people who do not use cars to get from place-to-place. These considerations would be pondered while a roadway improvement project is being designed rather than implemented alongside new development.

The intersection of Route 88, Route 70 and Princeton Avenue in Brick, N.J., Dec. 2023. (Photo: Shorebeat)

Complete Streets may include utilizing existing roadway width to add bike lanes, wider sidewalks and “shared use paths” which combine bicycle and pedestrian usage in an area separated from the lanes where motorized traffic flows.

While these measures could increase capital costs, they also could open up grant opportunities to implement bicycle and walker-friendly improvements and, ultimately, reduce crashes and save lives, the report said.

The planning board unanimously approved the traffic circulation plan re-examination, which will also be reviewed by the township council and incorporated into the township’s master plan, which governs how future zoning ordinances are crafted and creates legal standards developers must meet when applying for permits and variances.

Advertisement

Local Business

Mixed-Use Development Sought Next to Popular Point Beach Bar